Blown by a wind to Johnny Cash's resting place

An unexpected occasion to reflect on the convergence of worlds

Sitting on the bench beside their graves that pleasant April afternoon in Hendersonville, Tenn. is where these thoughts came together. But they didn't originate there. Nor was it only in the hours the Hoddinott clan — the trinity resident at the centre of the known universe — spent belting out harmonies to their recorded voices on the multi-interstate rip-up that got us here, and on other road trips as well. For, in spite of the obvious, this had not been a pilgrimage at all.

Drawn by duty

Something happened somewhere in the mix, I dare say, of the sometimes-inventive, sometimes-ridiculous harmonies (or the multiple layers of too-eager unison) we heaped upon the anesthetized vocals of Johnny Cash — and, where applicable, June (Carter) Cash — on the likes of “He Turned the Water Into Wine”, “If I Were a Carpenter”, “Were You There” (cue the three-tiered falsetto), “Country Trash” or “Jackson”. There re-awakened a dormant appreciation of the-black-and-the-beautiful contribution to music-that-tells-stories, and we found ourselves drawn by duty (and directed by the still, small voice of a connected mobile device) to their graveside.

But there is more to it.

Perhaps it’s just that I became aware of the interconnectedness of it all only while sitting on the stone bench in that quiet cemetery, staring pensively at the understated grandeur of their memorial, that made an otherwise touristy stop emotionally noteworthy. And, not in a small way, there was something curious about the youthful puffs of cotton candy clouds overhead, even this early in the season, bounding as they sailed the day, ricocheting off each other in playful silence.

Ambling slow an' free

Admittedly, I was already in a nostalgic frame of mind, here fresh (or scarred) from a losing quarrel about gravesite respect with the tuned-out leadership of the religious sect my late parents had given their lives to. A wandering mind, distracted from here, also ambling slow an’ free where it would: across state lines, over international boundaries and across chasms of time.

Not surprisingly, it lodged gently in a place where life was yet innocent and sweet: full of promise and possibility and naiveté. Here, the bringers of spiritual civility had granted us full-and-equal access to the fellowship of peons, and life was purposeful and musical and storied as we traversed the exciting regions of their multiverse at will, troubled none by how ruthlessly exact is the line dividing the realm of the elect from the realm of the elected ... um ... to do the bleeding.

You live, you labor, you die. That’s life.

Rich or poor in this unblemished world of ours, though, expectation was the beloved dead of all faith streams would be laid to rest in places made sacred both by blessing and by their having been reverently fenced off from roaming animals and the vulgarity of everyday life. (Still safely in the distant future would be the unthinkable scenario where hat-in-hand pleas and then determined appeals for such consideration would even be required, let alone fail to move the detached spirits of important heads-of-faith.) And Johnny Cash was here, sermonizing from an eight track on a car stereo the perfectly crafted profundity of poetic parallel that drew all things into a workable truth: “Mama’s turning leftovers into hash... And God’s got a heaven for country trash.”

Influential storytelling

I’ve never been a great fan of Johnny Cash the singer, as measured by the die-hard suitably costumed disciples one meets practically everywhere. Mainly for musical (not to be confused with musicality) reasons, though the whole Man in Black kitsch was also lost on me. The anticipated vocal lift that brings one to a new place partway through a song doesn’t occur often enough in his music to release me from the arguably OCD-induced bind its absence puts me in. That and the fact that I am a collector of albums more than a consumer of hits, and few Cash albums have satisfied my strict criteria.

But when they did!

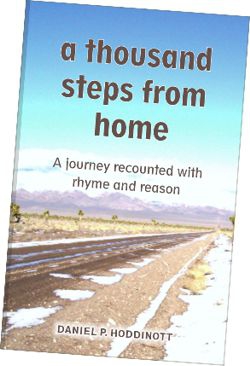

I was surprised to discover, when reviewing lives in this introspective space, just how influential his storytelling had been in my own musical pursuit. Even to including his 1973 album Any Old Wind That Blows on my short list of all-time greatest influences — which I then duly recalled.

That album was rife with vivid imagery, exemplified by the lyrically picturesque “Country Trash”. I might not have known, back then, what a doubletree is, or even a mackinaw for that matter, and certainly not that the moniker “country trash” probably referred to us in the eyes of the religioneers who would craft our way in spite of our spirit. (Believers tithing even as they bled in trenches, while those doing the ordering and collecting chose to reserve the monuments for their own ilk could count as evidence, one would suppose.)

All the while, Cash’s parallel between mama turning leftovers into hash and a splendid ending in store for those not appreciated here was resonating with far more clarity than were cold-hearted admonitions by the spiritual illiterati who would direct our paths. And even as the details of the lyric fell away over time, and the two parallel lines became erroneously re-sequenced in my memory, the vision and its essence had remained.

You could just picture the dirt-poor farmer in his fields, making the best of what was available. (I had never actually met a farmer yet, outside of storybooks, but presumed him, in the context of the lyric, to be the parallel of fishermen or woodsmen I did know: wholesome, decent, hard-working family men of few words but enduring deed.) You could picture the missus doing her thing with the leftovers. You could see him, sweat on his brow from the heat of the day, coming in at mealtime, hanging his hat on a nail by the door, then pointed wordlessly by his wife to the ewer on the wash basin — mid-stride, even, as she placed the last of the fixin’s on the table. You could see all these things as clearly as if you were standing in the doorway watching them. (Or were lucky enough to have had a place set at their table for you.)

Storytelling at its finest.

Companion forms of storytelling

“Simpleton” that he was, I imagine this “country trash” pausing to ask the blessing over the food before eating, too. Not in a reeled-off recitation by rote, which would be pointless to revere, but a heartfelt expression of humility and gratitude — for the day, for the food and for the company that had come their way.

I would later see this scenario for real, a thousand times, in the South. (It is the "Sapling Ridge" reference in my on-stage recitations.)

Planted also in my mind that summer of 1973 was the idea of country music and gospel music being, while not necessarily interchangeable, at least companion forms of expression recognized by the very same audience. This, too, I would come to verify through experience. In American culture it is thus, more so than in any other culture I have observed: two genres seemingly predisposed to warring have been, instead, historically joined at the hip.

The answer to the puzzle, I believe, is stated best in the Trace Adkins song, “Songs About Me”, which argues for the validity of country music while revealing the basis of its values:

'Cause it’s songs about me and who I am

Songs about loving and living

and good-hearted women, and family and God

Yeah, they’re all just songs about me.

A fan of where it's heard

I am not so much a fan of country music as I am of the segment of society it represents. Of course I am a fan of the storytelling, but even more of the places you hear it playing on the radio, or perhaps on the overhead.

It’s at the country store, where you spot a couple of youngsters heels-up into a horizontal freezer as they dig for ice cream, and when your turn comes the pleasant woman behind the counter asks about your day or what you’re up to, her smiling face juxtaposed interestingly against a hand-drawn cardboard sign just behind her that snarls: “If You’re Not 18 Don’t Even Ask for Cigarettes”.

It’s at the Food Lion parking lot, where a woman in a ponytail and a beat-up pickup truck — one arm and a whole pile o' tunes hanging out the window and only the heel of her other hand rotating the steering wheel — backs in one confident cut into the one remaining space.

It’s at the Cracker Barrel, where a couple with many more miles behind them than they have left to go exhibit neither complaint nor self-consciousness as he reaches across the table to cut up the catfish and to break apart a biscuit so she can dig in with her one good hand.

It’s at the end of a country lane, in a sprawling house whose occupants have dwindled to two but still smells like gingerbread — between snatches of news and weather on an old radio on a shelf in a sitting room about to be overtaken by dusk.

It’s at the edge of a sidewalk, beside the splayed-and-spewed toolbox and the man's legs sticking out from underneath a '67 Chevy.

It’s at the Ruritan Club fair, where country singers and gospel singers alike come off the stage (a backed-in flatbed trailer) to be herded into a place where smiling women, serving utensils in hand, wait behind heaps of salads and beans and fried chicken and — Lordy! Lordy! — arrays of homemade pies. And where equally pleasant men wait to take a seat opposite you, just to chat about ... stuff ... as you eat.

While I may not favor some themes broached in country music, and catch myself now and then smirking at some of the imagery foreign to my own experience, there is an overarching truth contained in the whole that resonates in me. For what country music does — and it does it very well — is capture the essence of that world where I’d rather be.

Anyone headed down to Jackson?